It was in the latter half of the 1980s that I realised that it was more effective to help a select few companies (private and public) to buy than it was to try to sell to them all. It was not a great revelation that suddenly hit me, but a thought that slowly matured in the context of a new job, writes Hans Peter Bech in this post.

Hans Peter Bech, cand.polit. (born 1951), is an author and consultant specialising in international business development in the software industry. He has published several books, articles, podcasts and videos on the subject and also advises companies all over the world.

In 1986, I accepted a job offer as sales and marketing director of a dewy startup. One that had invented a whole new way of doing things and didn’t yet have a single customer.

The products weren’t quite ready either, but on paper the concept looked very promising. As well as getting sales going once the products were ready, my job was to build an organisation that could scale the revenue we had decided would be generated through dealers. As the products had international potential, we also decided to start activities outside Denmark as soon as possible.

We were bootstrapped and therefore had very small budgets.

On a barren field

It was like starting on a completely barren field, with hundreds of big and small tasks ahead of me. During a run in the woods, it struck me that all the tasks were based on answering five simple questions:

- What kind of companies can get the most value from our products?

- Why will they buy them?

- When will they buy them?

- How will they buy them?

- How can we best help them make a decision?

These five questions became the guiding principles for the organisation of all our marketing and sales activities and also formed the core of the training of our own and our distributors’ sales and pre-sales people.

In principle, our product range was completely generic and could be used by all companies, public or private, large or small. And it soon became clear that we could not control to whom and how distributors chose to sell the product. We trained them thoroughly, but once they were unleashed, they were like spring cows in a lush pasture.

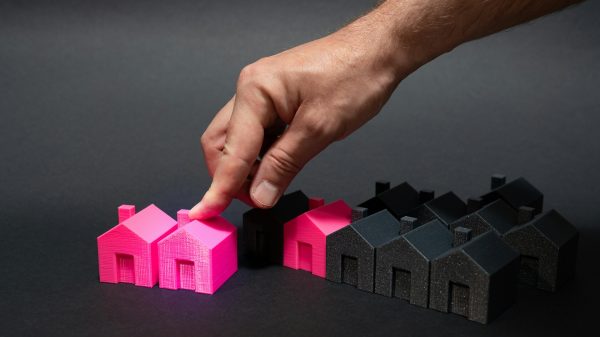

In return, we were able to determine the design of our own marketing materials and activities. We chose to focus on a fairly small segment of the market and targeted messages at the particular challenges they faced. From this starting point, the answers to the five questions were very concrete.

It was a huge success and convinced me that for a startup it is much more effective to help selected customers buy than it is to try to sell something to all of them. And although I’ve encountered a lot of scepticism about the word choices over the years, at no point did I think it was just a matter of semantics or a dispute over the emperor’s beard. Sales, in my view, remains most effective when seen as facilitating the buying process of selected customers.

What is selling anyway?

The discussion about sales or purchase facilitation is easily muddied if we do not put the same meaning into the terms. And we rarely do. While we can probably quickly agree on what is meant by the term “buying”, there are immediately much greater divergences in what the term “selling” actually covers. Helping customers to buy also easily comes across as cunning spin, where we are trying to coax money out of their pockets a little faster via a hidden agenda.

At an organisational level, I see selling as the part of revenue generation where, through an individual dialogue with each customer, we find the solution that offers the most value and that she can and will buy.

The confusion arises when we use the term sales for the whole revenue generation process. In the illustration, as far as new sales are concerned, only the two activities labelled WIN and MAKE should be called sales in my view.

Customer journey and buying process

In my previous job I had sold very capital intensive systems and knew that there was a difference between the customer journey and the buying process. The customer journey is the process by which the customer becomes aware of a need, over time determines how to solve it and selects which suppliers to involve. It is often referred to by the acronym AIDA, which stands for Awareness -> Interest -> Desire -> Action. The buying process is the last part of the process where the customer is approaching or in a BANT situation (BANT: Budget, Authority, Need, Time).

For the potential customers, the purchase of our product was a strategic and mission critical investment. If the products did not work, the customer’s business would grind to a halt.

We did not know which potential customers were in front of or could be motivated to invest in a solution based on our products, but we knew that it was far from all of them. In the market segment, for example, there were a number of companies and organisations that were very loyal to IBM (token ring) and would therefore be difficult to motivate for our technology (ethernet). But that was so much a personal issue. Not all IBM customers slavishly followed the vendor’s recommendations.

Our marketing materials and activities had to support all stages of the customer journey, while reserving scarce manpower resources for customers who were in or entering a current buying process.

An attempt at a definition

Against this background, our definition of the two processes (sales and purchase facilitation) came to look like this:

Sales, for most, is about trying to convince everyone they come into contact with to buy their product. They all highlight the benefits of the product and the values it can create in general, trying to persuade customers to buy. They believe that if the customer is informed thoroughly enough about what the product can do, she will find the budget and buy. Sales people in this category are super enthusiastic, talk a lot, like to do product demos and love to use PowerPoint presentations.

Buying facilitation requires more time per customer, so start by making sure you only work with customers where your product has the potential to create far more value than the price you’re asking. Then assess whether you can support the customer’s buying process at all. If this is the case, and it is likely that the choice of supplier could turn out in your favour, then you register the customer as a prospect and invest resources in the process. Buying facilitators ask a lot of questions, listen a lot, are sceptical and often say no thanks.

So how did we practice purchase facilitation when customers didn’t know who we were and what we could do for them?

Effective revenue generation

All potential customers are always on a customer journey, but they are rarely in a buying process. The marketing department’s job was to build relationships with potential customers and detect when there were signs that a buying process was underway. At that moment, the sales department had to get involved.

The big question was (and still is) whether we could activate a buying process. Could we activate a latent need and thus trigger a BANT situation? We thought we could, but we couldn’t know in advance which potential customers could do it.

So we invested all our earnings in two marketing programmes:

- Working with dealers’ existing customers.

- Marketing to potential customers in the core segment.

Dealers’ customers

Our dealers were already in contact with customers who might need our product. It was relatively easy for them to find the relevant contacts and get speaking time. We developed presentations, whitepapers and reference stories that could be used to inform customers about what our products could do and what other customers were using them for. We trained dealers on how to use the material and offered free pre-sales assistance when meeting or preparing proposals for the large companies in the core segment.

Once a dealer had closed a few large orders, they understood the concept and became self-sufficient.

Marketing

We were operating at a time (1986) when there was no internet, social media or email, so marketing was via PR, adverts, exhibitions, direct mail (with stamps on it!) and the telephone. The fax was becoming widespread and could also be used. Together with dealers, we used all channels to reach potential customers we were not already in contact with.

This cost money and, as I said, we invested all the money we earned in marketing. We also used another trick to generate additional cash flow, which you can read about here.

Contacting potential customers and generating interest was not considered a sale. That was marketing. Visiting a potential customer and presenting our solution was also a marketing activity.

Sales only started when the customer started asking specific questions and when we could identify a BANT situation. At that point, we moved from marketing to purchase facilitation. We had arguably the best buy facilitators in the industry, who both knew our products down to the last detail and were able to quickly understand the customer’s problem. They were monster people, but they were worth every penny.

Although our dialogue was typically with the organisation’s CIO or one of his department heads, the motivation for the project always had to be found in the business. If the IT people couldn’t answer our questions adequately, we would take the dialogue to the business ourselves. If we couldn’t, we pulled out of the project. We saw it as our job to deliver business value, not just products.

Timing

Our timing was perfect. We hit a gap in the market that had arisen as a consequence of major and rapid shifts in the IT platforms that businesses were using. The very large organisations in particular had mammoth challenges that we could solve. Others could solve them too, but our solution was more elegant, cost less and we were better at marketing and helping customers prepare an investment case.

We never pushed and we didn’t discount. Instead, we tried to understand why customers were interested in our products and what they expected to get out of them. Maybe there was something we could do to make their investment case even better.

In conclusion, I must confess two things:

First, our success was largely due to the fortunate timing of our products coming to market at just the right time. It’s easier to practise purchase facilitation when you don’t have twenty competitors breathing down your neck with products that are confusingly similar to yours.

Secondly, we managed to win a big case very early on with a very large, well-known and well-known company. With that reference in hand, the guard at other large companies fell much more quickly. We had managed to jump the innovation gap very early on.

Our window of opportunity lasted only a few years. After that, alternative, commoditised and even cheaper solutions had entered the market. So our concept only proved competitive for a short number of years.

You can try to facilitate purchases all you like, but if your product does not solve a critical problem for your chosen segment and has some very obvious and clear benefits, you do not have the clout to get close to your customers.

Sales without salespeople

Particularly in tech and software, a number of companies have managed in recent years to find a revenue generation process that doesn’t need a sales pipeline at all. This is a huge advantage, because both sales and purchase facilitation are costly and difficult.

But for most, that option is unfortunately not possible. Not only do many B2B products require individual dialogues with customers before they can make a decision, but we often have to command their attention to build awareness of our existence and what we offer. When this is the case, I remain convinced that purchase facilitation is the most productive mindset.

The post “It’s more effective to help selected customers buy than to try to sell something to all of them” appeared first on startupmafia.eu.